Learning Disposition

Fellow: Noah Rachlin

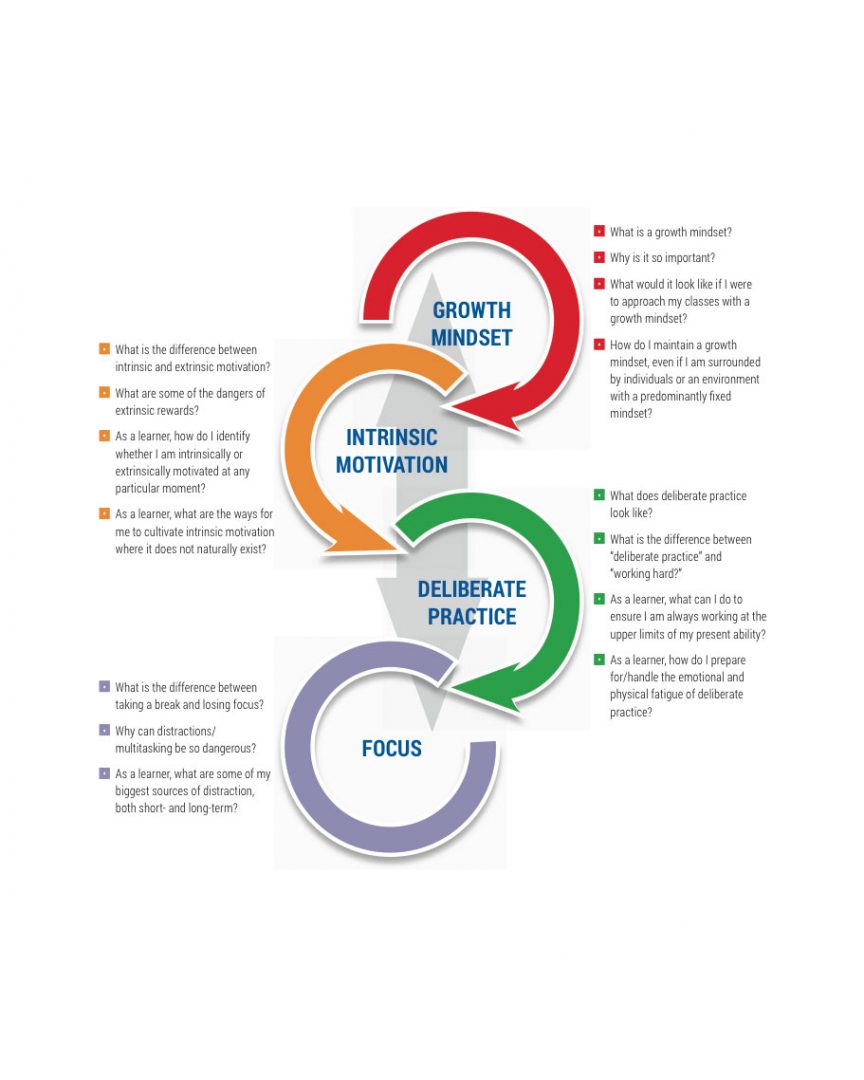

A compelling body of research has shown that helping young people to respond positively to challenge and struggle is critical to how they learn and what they learn—in school and throughout their lives. Whether in the classroom or outside of it, engaging with a new community online, or developing a new skill, young people must have the capacity to understand failure and adversity as natural parts of the learning process. Informed by research in the field, Noah Rachlin is leading an effort to help students and teachers see mistakes not as impenetrable roadblocks but as natural parts of the learning process. Rachlin has defined this practice as “learning disposition,” which he breaks into four key concepts: mindset (“I believe it is possible to improve”); motivation (“I want to improve”); deliberate practice (“I’m going to work at the upper limits of my ability to improve.”); and focus (“I will commit myself to this work over time”). He believes that these components are essential to any kind of learning encounter and can serve young people in powerful ways, enabling them to become agents in their own learning.

PROJECT OVERVIEW

Learning is hard.

Trying to understand a complex mathematical proof, revising a paper for a history or English class, conducting a science experiment, and learning a new language are especially difficult tasks. Furthermore, these struggles do not exist only within the four walls of a traditional classroom. Every day, students also face challenges as they practice for piano recitals, refine their jump shots, or work to further develop their abilities as budding photographers or writers or scientists. Yet, too often, a lack of immediate mastery can be perceived as a sign of weakness—or worse, inability—and their response is, “I can’t do that.”

With pervasive issues such as these in mind, Noah Rachlin, instructor in history and social science and Tang Institute Fellow, is working on his project, “‘I Can’t Do That…Yet’: Cultivating a Learning Disposition.” The project—which explores the concepts of mindset, motivation, deliberate practice, and focus—aims to help cultivate in students a “learning disposition” so that they are prepared to overcome the inevitable challenges of learning both in and out of the classroom.

Rachlin is considering how educators can help students transition from thinking or saying, “I can’t do that” to “I can’t do that yet.”

In doing so, Rachlin believes that educators can empower young people to be lifelong learners who are comfortable embracing difficult tasks because they have come to perceive challenges as natural and essential components of human growth and development.

In place since 2014, the curriculum and ideas associated with “I Can’t Do That…Yet” represent initial strategies aimed at helping students cultivate a learning disposition. Which strategies and interventions have proven to be most effective in your own context? How have you supported efforts aimed at encouraging students to embrace the learning process? We look forward to hearing your feedback, insights, and additional ideas related to building a learning disposition.

Project Materials

The cultivation of a learning disposition, understood by this project as a set of qualities that help students respond positively to the inevitable challenge and struggle of learning, is a crucial component for successfully preparing and educating a 21st century student. By creating a toolkit for teachers and educators, Tang Fellow Noah Rachlin provides resources and guidance to foster the development of a learning disposition in every student, in every classroom

Key Concepts

Noah highlights the key concepts and what matters most when undertaking this work.

Classroom Strategies

Three example strategies that Noah has implemented in his own classroom teaching.

Curriculum in Action

Noah’s notes from his weekly sessions illustrate how to put this curriculum into action.

Featured Articles

Mistakes Were Made — Harvard Graduate School of Education

Learning Disposition — NAIS (National Association of Independent Schools)

Additional Resources

Mindset

Motivation

Deliberate Practice

Focus

Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset

In a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment. Virtually all great people have had these qualities..

In a fixed mindset, people believe their basic qualities, like their intelligence or talent, are simply fixed traits. They spend their time documenting their intelligence or talent instead of developing them. They also believe that talent alone creates success—without effort.

–from Carol Dweck’s Mindset: The New Psychology of Success

- How not to talk to your kids: the inverse power of praise by Po Bronson NY Magazine

- What if the Secret to Success is Failure by Paul Tough NYT Magazine

- The Learning Myth: Why I’ll Never Tell My Son He’s Smart by Salman Khan

- Growth Mindset: A Driving Philosophy Not Just a Tool by David Hochheiser

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

With the exception of rote tasks that do not require any creativity, in a great many ways, intrinsic motivation leads to far more productivity and creativity than extrinsic motivation and is less susceptible to corruption, dishonesty, and abuse.

Intrinsic motivation or what Daniel Pink refers to as “Type I Behavior” “depends on three nutrients: autonomy, mastery, and purpose…is self-directed…is devoted to becoming better and better at something that matters and…connects that quest for excellence to a larger purpose.”

- What Keeps Students Motivated to Learn? by Katrina Schwartz

- SMART: Goal Setting With Your Students by Maurice J. Elias

- Jerry Seinfeld’s Motivation Strategy by Gina Trapani

Deliberate Practice

“Struggling in certain targeted ways—operating at the edges of your ability, where you make mistakes—makes you [better]…experiences where you’re forced to slow down, make errors, and correct them—as you would if you were walking up an ice-covered hill, slipping and stumbling as you go—end up making you swift and graceful.” – Daniel Coyle

“We think of effortless performance as desirable, but it’s really a terrible way to learn.” –Robert Bjork

- How to Design Right Size Challenges by Suzie Boss

- What’s The Sweet Spot of Difficulty For Learning by Annie Murphy Paul

- Struggle for Smarts How Eastern and Western Cultures Tackle Learning by Alix Spiegel

- “Try, Try Again? Study Says No | McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT by Anne Trafton

Focus

Multi-tasking is a myth. The brain cannot actually focus on more than one thing at once. Individuals who present as really good “multi-taskers” actually just have a very strong working memory.

Interruptions are particularly detrimental to performance and have been shown to cause an average of 20% decrease in academic performance in certain studies. In a research study with a particular focus on text message interruptions, students lack of cell phone use led to a full grade and a half better performance.

- Say “No” to Interruptions, “Yes” to Better Work by David Price

- Are Your Students Engaged? Don’t Be So Sure by MindShift

- Teaching Students to Ask Their Own Questions Can Yield Big Results by Dan Rothstein and Luz Santana

From the Blog

"Part Classroom Teacher/Part Motivational Speaker" appeared in the fall issue of NAIS's Independent Teacher Magazine.

Duckworth encourages motivation and creating the opportunity for practicing character are critical for young people

Discussion May 15 will focus on the psychological environment that increases student persistence